BC’s Quiet Shelving of “Alternative Shelter” Law Underlines the Need for a Human Rights-Based Approach to Tent Cities

Stepan Wood

Professor and Canada Research Chair in Law, Society and Sustainability,

Jul 17, 2024

On July 10, 2024, the government of British Columbia quietly notified selected stakeholders that it has shelved the new law on homeless encampments it introduced and passed in November 2023.

This decision marks the end—for now—of one of the province’s most problematic recent legislative responses to tent cities.

It is an opportunity for the province and municipalities to go back to the drawing board and develop a human rights-based policy response to tent cities in partnership with people with lived experience of homelessness and their trusted allies.

This is not just a BC story. It has implications for communities across Canada and around the world that continue to resist putting the rights, interests, dignity and agency of society’s most marginalized members front and centre in efforts to resolve the crisis of homelessness.

Bill 45: Igniting a controversy

The provisions regarding tent cities were tucked into the omnibus Bill 45, which was introduced in the BC legislature in early November, 2023. These provisions would apply whenever a municipality sues for an injunction to enforce its bylaws against someone sheltering in a homeless encampment. In short and cryptic language, Bill 45 stated that alternative shelter is “reasonably available” to a person sheltering in a homeless encampment if the person may stay there overnight, the shelter is staffed when in use, and the person has access to a bathroom, shower and one free meal a day at or near the shelter. If a shelter meets this bare-bones description, it is deemed to meet the basic shelter needs of tent city residents.

The government claimed that the bill was intended to provide clarity and consistency around the shelter standards cities must meet in order to be able to decamp a homeless encampment. Premier David Eby claimed that the bill “reflects existing court decisions around removing encampments so that municipalities ‘meet a minimum standard of moving displaced people into shelter that’s dignified and safe’.”

The bill immediately raised a storm of controversy. It left key terms undefined and ambiguous, like “homeless,” “encampment” and “near.” It failed to specify what follows, legally, if a court finds that available shelter options meet the statutory definition.

But most significantly, it exposed deep disagreements about the minimum shelter standards municipalities must meet before they can ask a court to evict tent cities from municipal land.

On one hand, the First Nations Leadership Council, BC’s Human Rights Commissioner, the Federal Housing Advocate, other housing rights advocates, the BC Green Party leader and researchers including me slammed the bill for trampling on the human rights of unhoused people and making evictions too easy.

They argued that the bill lowered the standard for injunctions set by the courts, ignored Indigenous peoples and their rights, disregarded the multiple intersecting barriers that make shelter spaces practically inaccessible to many unhoused people, denied unhoused people’s pressing need for daytime shelter and storage, and was drafted without consulting those affected by it.

As a BC Civil Liberties Association staffer told the CBC, the bill tried “to impose a very low level, one-size-fits-all solution on a group of people that have very diverse needs that are often not met by these bare bones thresholds.”

Opponents also pointed out that the bill, as drafted, did not even require shelters to provide any place to lie down and sleep. The absurd implication, as I and others pointed out, was that in principle, a 24-hour Tim Horton’s could qualify as “reasonably available alternative shelter” for purposes of a decampment injunction.

The most comprehensive statement of these critiques was contained in an open letter to the government from more than 60 lawyers, activists, volunteers, community workers, researchers and people with lived experience of homelessness. I was part of the core drafting group and sent the letter to the Premier, Attorney General and Housing Minister on November 21, 2023.

The letter, which received significant public attention, urged the government to withdraw the bill and develop a policy response that adopts the rights-based approach set out in the National Protocol for Homeless Encampments in Canada and endorsed by the Federal Housing Advocate.

READ THE NOVEMBER, 2023 OPEN LETTER

On the other hand, local government organizations claimed that Bill 45 would make tent city evictions practically impossible and encourage more encampments. They complained that no BC municipality has enough shelter facilities that meet the bill’s standard, pointing to the huge disparity between the number of unhoused people and the number of available shelter spaces throughout the province.

They argued that the bill would make injunctions highly unlikely, depriving municipalities of a key tool to manage encampments and forcing them to bear the burden of the province’s failure to provide adequate shelter spaces, which is a provincial, not municipal, responsibility.

Coincidental timing

The controversy over Bill 45 unfolded against the backdrop of ongoing academic and other research into tent city causes, effects and solutions. Coincidentally, the bill was introduced just days after the public launch of two research reports on homelessness involving researchers at the University of British Columbia.

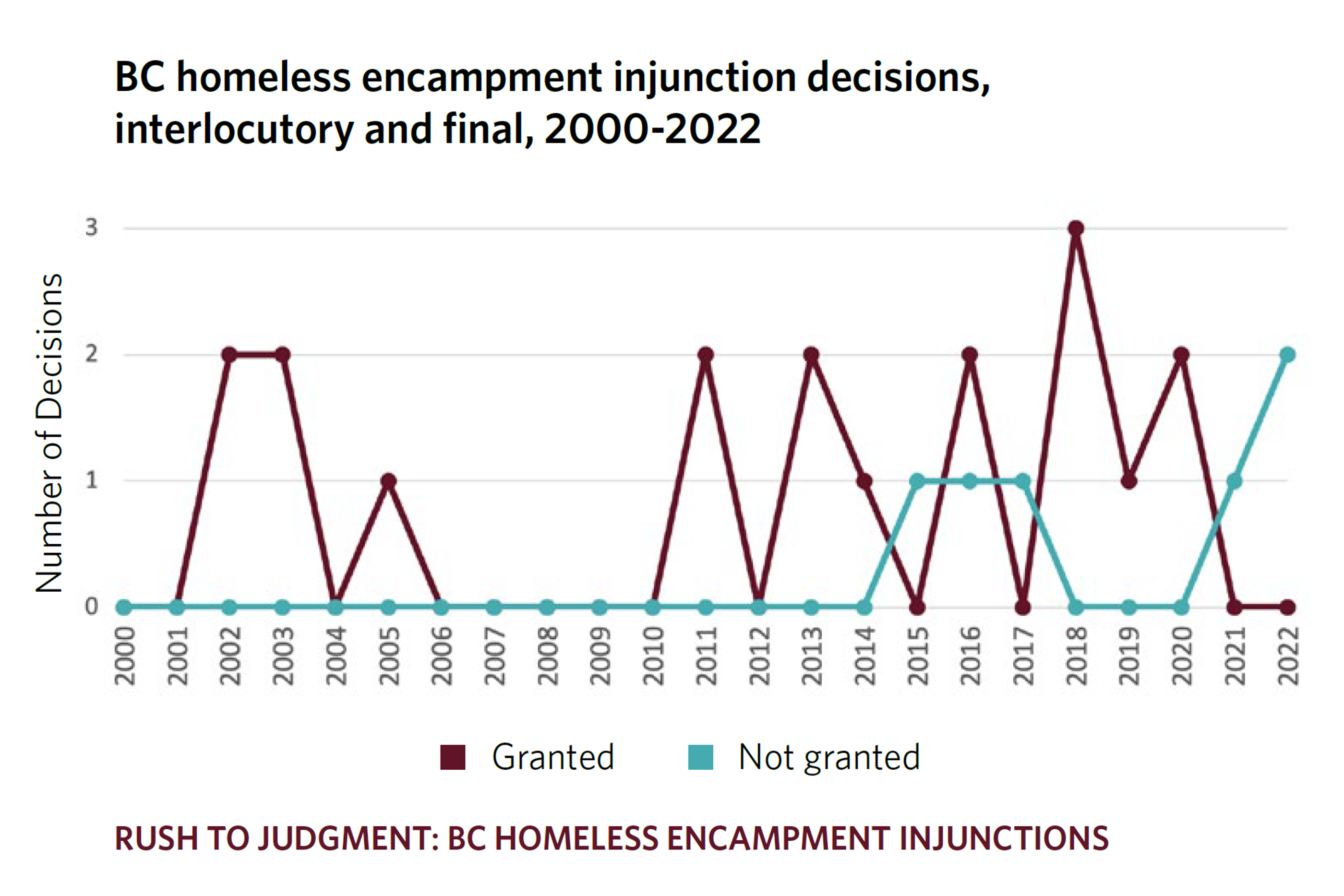

On October 26, 2023, UBC’s Centre for Law & the Environment hosted the launch of my report of the first systematic study of tent city injunction decisions in BC. It contained both good and bad news for precariously housed people.

The bad news was that BC courts have generally been alarmingly eager to grant injunctions to clear tent cities from government-owned land, with an astronomical 85% grant rate for interlocutory injunctions. These injunctions are granted before the government has proved its case, and usually bring the lawsuit to an end as tent city residents are scattered to the four directions. Moreover, BC courts often misapply the law and discount or ignore encampment residents’ evidence in the process.

The good news was that this tendency is waning. In recent years BC courts have become more reluctant to grant injunctions and more sensitive to the benefits of encampments, the harms of continual displacement, the tendency to exaggerate the harms of encampments, the need for 24/7 shelter and storage, the practical inaccessibility of existing shelter alternatives for many encampment residents, the futility of evicting one encampment after another, and the intersection between homelessness and colonial oppression of Indigenous peoples.

READ THE "RUSH TO JUDGMENT" REPORT

WATCH THE RECORDING OF THE LAUNCH EVENT

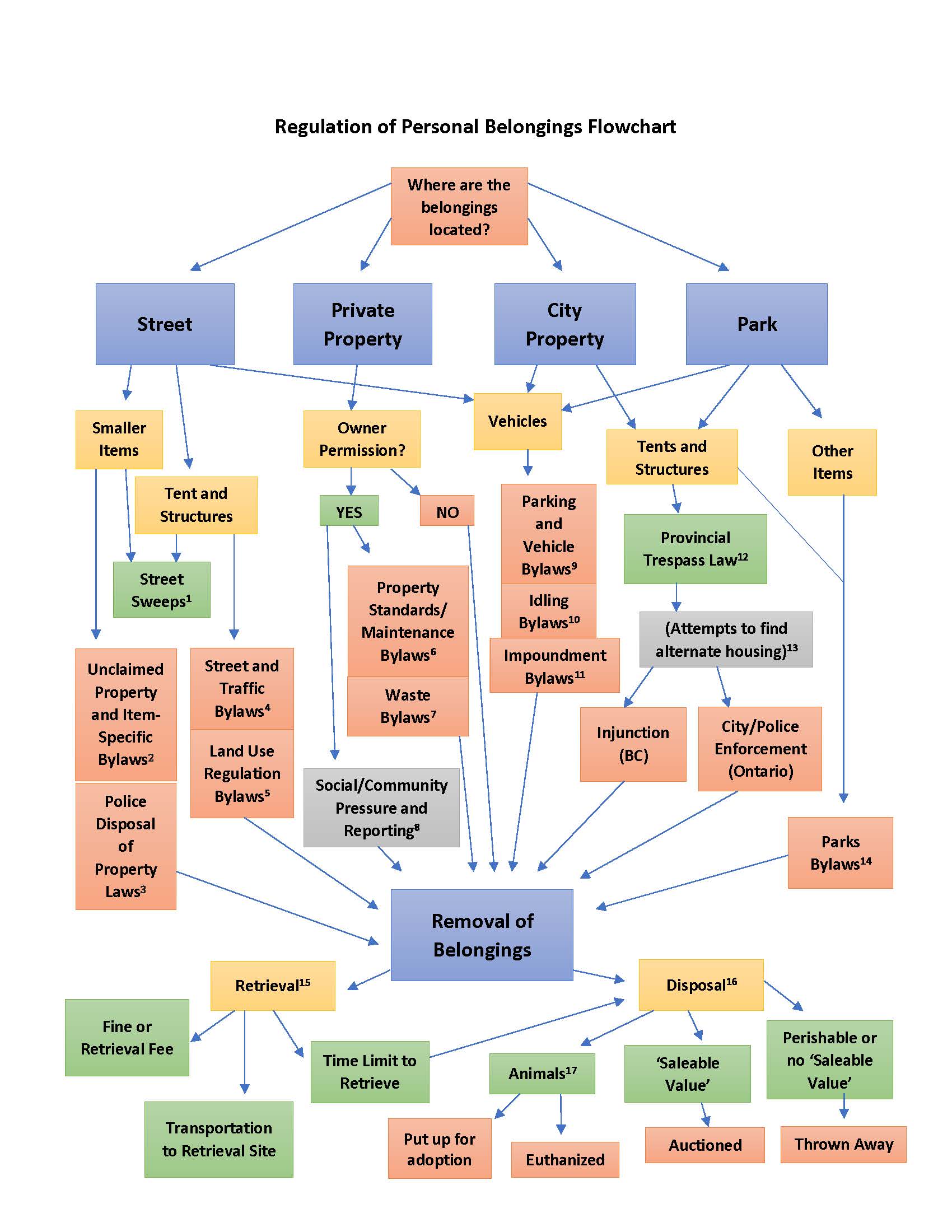

A week later the Centre hosted launch of the “Belongings Matter” report and website by my UBC colleague Alexandra Flynn and her collaborators including Nicholas Blomley of Simon Fraser University and Marie-Eve Sylvestre of the University of Ottawa.

This report documents how the laws and rules that apply in various public and private spaces effectively strip unhoused and precariously housed people of their right to own their own personal belongings. It details how the complex and byzantine rules and regulations that govern sidewalks, parks, shelters, transitional housing, storage facilities, rooming houses, single-room accommodations and insecure rental housing routinely result in the seizure and destruction of unhoused and precariously housed people’s belongings, almost always without effective remedies.

Both reports were in formats amenable to policy makers and attracted significant media attention. Yet neither they nor any of the many other examples of policy-relevant research documenting the ways in which legal systems can contribute to the crisis of homelessness, appear to have informed the drafting of Bill 45 in the slightest degree.

ACCESS THE "BELONGINGS MATTER" REPORT

WATCH THE RECORDING OF THE LAUNCH EVENT

The province backs down—sort of

Academic research may not have stopped the government from pushing a regressive statute through the legislature, but it informed the public pressure campaign that led to the government’s decision to backpedal.

Faced with intense opposition from municipalities and other stakeholders, the government blinked. But instead of withdrawing the bill, as all critics demanded, the Premier promised to push it through the legislature but delay bringing it into force to allow further consultations.

The government kept this promise, in part. It rushed this and several other important housing bills through the legislature with little debate, inserting a provision that the “alternative shelter” sections would come into force by regulation at an unspecified future date.

Keeping the promise to consult further with relevant stakeholders before bringing the law into force was another matter.

As I wrote with colleagues in an op-ed piece, “Passing a bad bill but holding off implementing it is no solution.” What was the point of consultation if the law was already on the books and would not change? Expressing the same sentiment, opposition politician Mike de Jong called the government’s approach “highly presumptuous” and “a disservice to the notion of true consultation.”

Consultation—what consultation?

More importantly, the government was rather selective about whom it consulted. We know it consulted high-level organizations and officials including the Federal Housing Advocate, the BC Human Rights Commissioner, the Union of BC Municipalities and the First Nations Leadership Council.

These are certainly important stakeholders, but there is little evidence that the government consulted individuals with lived experience of homelessness or the frontline advocates and service providers they trust to advance their interests—many of whom signed our open letter.

Shortly after the bill was passed, I sent a follow-up message to the Premier, Attorney General and Housing Minister on behalf of an updated list of 161 open letter signatories from 31 organizations that advocate for and work with unhoused people, along with 12 post-secondary institutions and 9 law offices. We emphasized the importance of consulting people with lived experience and those they trust, and invited the government to use our list of signatories as a starting point.

In a reply email, the premier’s office said they had asked the Ministry of Housing to follow up with us directly and assured us that the appropriate ministry official would respond at their earliest opportunity.

That was the last we heard for two months, during which none of the signatories or their organizations reported being consulted by the government about the bill.

Then on February 5, 2024, we received a letter from the Housing Minister stating that the consultations promised by the government were already underway and would finish in early 2024. The letter did not suggest that any of our signatories or their organizations would be consulted.

The Federal Housing Advocate weighs in

A week later, the Federal Housing Advocate, Marie-Josée Houle, issued her long-awaited final report on homeless encampments. The report powerfully reinforced the critiques of Bill 45 advanced by us and others. Calling encampments a national human rights crisis, she emphasized that they are an effort by unhoused people to “claim their human right to housing” and “are often people's only housing option, or the only option that meets their needs for safety, security and dignity.”

The report called on governments to immediately end all forced evictions of encampments, which it characterized unequivocally as a violation of human rights.

Let's be clear: Bill 45 is designed to authorize forced evictions of encampments. That is precisely what a court injunction to clear an encampment does. Instead, the Advocate urged governments to support encampments with basic necessities, including clean water, sanitation, food, heating, cooling, accessibility, health care and harm reduction; and co-develop encampment-related policies with encampment residents.

Further, the report insisted that laws and regulations must not further destabilize encampments or expose residents to greater risk of harm, and that police, bylaw officers and emergency services should halt surveillance, harassment and confiscation of belongings. It called on senior levels of government to ensure that municipalities have the resources and powers they need to uphold encampment residents’ rights and fulfill their urgent needs—not to obtain injunctions evicting them.

The report also called on all governments to apply a human rights-based approach to tent cities that “recognizes and addresses the distinct needs of First Nations, Inuit and Métis individuals, Black and other racialized individuals, women, 2SLGBTQQIA+ individuals, people fleeing gender-based violence, youth, seniors and people with disabilities.”

Finally, the report called on all governments and service providers to work to remedy the structural barriers that render existing emergency shelters inaccessible or inappropriate for many unhoused people—quite the contrary of Bill 45’s effort to authorize decampment injunctions despite these well known barriers.

Increasing the public pressure

Frustrated with the lack of meaningful engagement and galvanized by the Federal Housing Advocate’s report, we launched an online letter-writing campaign in March 2024, graciously hosted by the BC Poverty Reduction Coalition, demanding that the government “sit down with precariously housed people and those they trust to create a policy framework that seeks to fulfill their rights to life, health and housing instead of seeking to justify forcibly evicting them from their homes.” The letter emphasized that this means meeting with tent city residents and the organizations and individuals they trust.

The letter insisted that the “alternative shelter” law must go, and summarized its faults:

It facilitates forced evictions of tent cities. It ignores the barriers many precariously housed people face to obtaining shelter, and the profound harm they suffer by having to pack up and move their homes and belongings every day. It says nothing about how evictions are carried out. It does nothing to ensure that tent cities meet residents’ basic needs. It allows outcomes that infringe residents’ rights and dignity. And it ignores the rights of Indigenous peoples, who are disproportionately represented in the unhoused population.

Once again, it called on the government to respect the principles of a rights-based approach, namely:

- Recognize residents of tent cities as rights holders;

- Engage meaningfully with and ensure effective participation of tent city residents;

- Prohibit forced evictions of tent cities;

- Explore all viable alternatives to eviction;

- Ensure that any relocation is human rights compliant;

- Ensure tent cities meet basic needs of residents consistent with human rights;

- Ensure human rights-based goals and outcomes, and the preservation of dignity for tent city residents; and

- Respect, protect and fulfill the distinct rights of Indigenous peoples in all engagements with tent cities.

The letter closed by emphasizing that precariously housed people and those they trust were “ready and waiting to sit down with you.”

At least 286 individuals eventually sent copies of the letter to the government before we closed the campaign in July 2024. But still, none of the organizations or individuals in our group reported being consulted about Bill 45.

READ THE SPRING 2024 OPEN LETTER

The province shelves the law

That was how things stood until July, 2024, when the Ministry of Housing quietly sent letters to selected stakeholders, including the UBCM, announcing that the government had decided not to bring the alternative shelter law into force at this time, because it had learned that “the amendments did not provide enough clarity for a common understanding of ‘reasonably available alternative shelter’ and the contexts under which the description should or could apply.”

The Ministry claimed that the government had “engaged with partners to better understand issues and concerns,” including “Indigenous partners and First Nations, Local Governments, community organizations, National and Provincial advocacy groups, law enforcement, and communities.” As far as I know, these consultations did not include any of the signatories of our November 2023 open letter.

The announcement was welcomed by the UBCM, which reiterated that “No one really has that type of shelter. Also, they don’t have enough, or the quality, that is specified in that legislation.”

This admission simply reinforces how far BC is from having a defensible approach to tent city injunctions. Municipalities cannot even satisfy the bare bones standard of Bill 45, let alone the standard of practical accessibility increasingly demanded by the courts, much less a human rights-based standard.

Bill 45 is not dead, however. The province could still bring it into force at any time.

An opportunity to return to the drawing board

I can only hope that this episode demonstrates to the province and municipalities the importance of going back to the drawing board to craft a policy response to tent cities with the people who live in them and their trusted advocates, not just with stakeholders that governments pick themselves or feel they cannot afford to ignore.

The letter announcing the shelving of the alternative shelter law noted that “the province is developing a Provincial Encampment Response Resource in collaboration with BC Housing, First Nations, Indigenous and community organizations, Local Governments, and people with lived experience.” This resource, which is slated for launch this summer, will summarize provincial policies, good practices and resources for communities responding to encampments, “with a focus on coordination, partnership, and ensuring people-centered, culturally safe responses.”

The development and issuance of this resource will be the next test of the province’s willingness to adopt a rights-based, consultative approach to tent cities that gives unhoused and precariously housed people a lead role in the development and implementation of policies that affect them.

Let us hope it does better this time around.

- Centre for Law and the Environment