Off the Mark: Time for Canadian Airlines to Transition Away from Carbon Offsets?

Tyler Murphy

Allard JD Graduate 2024

Aug 5, 2024

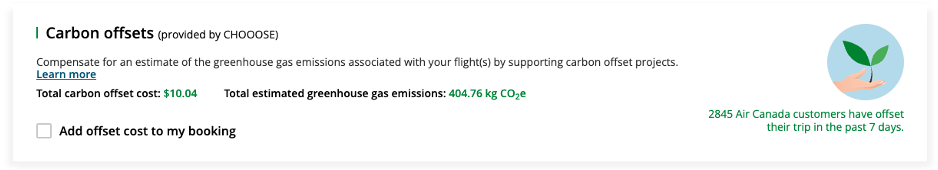

Have you ever experienced this: moments away from booking a flight, you are suddenly prompted to pay an additional fee to offset your share of the flight’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions? The emissions associated with a round-trip Air Canada flight between Vancouver and Toronto can be offset for as little as $10, yet the International Air Transport Association (IATA), which represents the world’s largest airlines, including Air Canada and WestJet, reports that a mere 1-3% of passengers buy voluntary offsets.

Despite this low uptake, airlines continue to be some of the largest purchasers of carbon offsets.

In 2022, Air Canada revamped its carbon offset program by dropping Canadian-based offset provider Less Emissions in favour of global climate technology firm CHOOOSE. Air Canada has evidently bet that take-up is due for an increase. Though in a time when carbon offsets’ effectiveness as a tool to tackle climate change is increasingly being cast into doubt, it may prove to have been a risky bet.

How exactly do carbon offsets work?

Carbon offsets enable individuals or companies to purchase “credits” that help finance certified third-party projects that aim to reduce GHG emissions. In other words, an airline passenger who voluntarily purchases a carbon offset will compensate for their share of their flight’s estimated emissions by supporting a project that reduces or avoids an equivalent amount of emissions elsewhere in the world.

Projects can involve tree planting, forest preservation, the capture and destruction of landfill methane, and clean energy infrastructure such as wind farms. Air Canada customers’ money is directed to one of CHOOOSE’s six offset projects around the world, including two in BC’s Great Bear Rainforest.

In addition to the sellers and purchasers of carbon offsets, the system also requires the involvement of independent third-party “certifiers” who audit and verify carbon offset projects. Purchasers of certified project offsets will often market themselves, their activities, or their products, as “net-zero” or “carbon neutral” to their customers.

Two of Air Canada’s selected carbon offset projects seek to preserve parts of BC’s Great Bear Rainforest, home of the endemic Kermode bear. “Ursus americanus kermodei, Great Bear Rainforest 1” by Jon Rawlinson is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Who buys them?

Governments and high-emission businesses are the main purchasers of carbon offsets. The aviation industry represents a significant portion of the latter, with almost every major airline, including 15 Canadian operators, offering an offset-based program to its customers. This is unsurprising given that the industry as a whole accounts for around 2.5% of global CO₂ emissions, which rises to 3.5% when taking non-CO₂ impacts on climate into account.

Air Canada, like all other IATA member airlines, has committed itself to achieving net-zero emissions by 2050. But airlines disagree over the role, if any, that carbon offsets should play in achieving that goal. United Airlines, for instance, has pledged that it will pursue net zero without relying on carbon offsets at all, and will instead focus on “in-sector emissions reductions and carbon removal technologies” moving forward.

What is the controversy with carbon offsets?

There has been a growing scientific consensus in recent years that the majority of carbon offset projects are unlikely to achieve the emission reductions they promise.

One reason is that many offset projects are simply never completed for one reason or another. Another relates to the inherent difficulty of quantifying the effects of such projects or the damage they purport to avoid.

In 2021, a joint investigation by the Guardian and Greenpeace concluded that offset programs relied on by major airlines were based on a flawed calculation system that likely produced an inflated picture of their effectiveness. The investigation looked at 10 forest protection projects that had been certified by Verra, a US non-profit that administers the Verified Carbon Standard (VCS)—the world’s leading carbon credit standard.

Projects typically estimate the emissions they prevent by predicting how much deforestation would have occurred without them. The investigation found that predictions were often inconsistent with previous levels of deforestation in the areas and in some cases, the deforestation threat may have been overstated. The investigation also highlighted concerns with reversibility (i.e., you could buy an offset and the forest could be cleared or burned the next day), and with proving that the project itself made a difference to the outcome.

These concerns persisted. In 2023, the Guardian undertook another joint investigation, this time revealing that over 90% of Verra’s rainforest offset credits are worthless—likely to be “phantom credits” that do not represent any genuine carbon reductions. The 2023 investigation produced a number of jarring figures: the deforestation threats were again being overstated, this time by an average of 400%; rainforest projects comprise 40% of all the credits certified by Verra, of which 94% yielded no benefit to the climate; and at least one project had experienced human rights concerns.

The frailties of project certification have been on display in Canada recently, as well.

In May 2023, the Alberta government approved 25 charges each against Canadian carbon offset certifier Amberg Corp. and its senior environmental regulatory coordinator, Olga Kiiker, for allegedly providing false and misleading information, providing functions of a third-party assurance provider without the required qualifications, and failing to comply with the relevant regulations.

This marked the first time a Canadian province has brought charges against a certifier. Ms. Kiiker pled guilty to one count, had the remaining 24 dismissed, and was sentenced to a $10,000 fine in November 2023. She penned an apology letter as part of a creative sentencing order, in which she outlined how she forged signatures and impersonated another employee to conduct third-party verifications, while imploring others to “learn from [her] mistakes.” All charges against Amberg remain unresolved. While Amberg was not in the business of certifying offsets for airlines, the case still underscores the inherent shortcomings that have plagued the carbon offset industry for decades.

Since 2007, Alberta has run a mandatory carbon offset system for large emitters, such as oil and gas companies, landfills and food processing firms. “20130811-164-of-365” by Wilson Hui is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Time to offload the offsets?

Given the mounting opposition to carbon offsets, it may seem logical for airlines to completely transition away from such programs in the coming years. However, this is likely easier said than done.

Most Canadian airlines will continue to have offsetting obligations for the foreseeable future under the United Nations’ Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA), which Canada has committed to implementing domestically.

Further, carbon offsets can provide some tangible benefits that may justify continuing with some level of offset programming in the future. Despite their well-documented flaws, many projects still do valuable conservation work and funnel much-needed financing toward deserving causes.

It is also true that many of the other measures advocated for by critics of offsets, such as sustainable aviation fuel, electric aircraft, or atmospheric carbon capture technologies, are many years away from commercial viability. Therefore, offsets serve as a valuable tool to address the aviation industry’s emissions in the interim.

However, the drawbacks are too glaring to overlook. In addition to those highlighted above, perhaps the most potent critique from experts is that offsets actually exacerbate the climate crisis by allowing the aviation industry to delay desperately needed action and regulation that would meaningfully contribute to global emissions reductions.

Ultimately, the best path forward for Canadian airlines is to follow in the footsteps of United Airlines and transition away from offsets while shifting focus toward efforts that are more likely to achieve the lofty goal of net zero by 2050.

- Centre for Law and the Environment