Nuclear Waste Disposal: Finding a home for radioactivity

Elvis Cheung

JD Candidate

Feb 10, 2023

Much public attention has converged around the role of nuclear power in the clean energy transition. Behind visions of a new atomic age set out in the 2018 Canadian Roadmap for Small Modular Reactors, the regulatory regime for managing nuclear waste reveals a complicated reality.

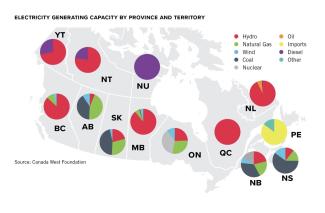

In 2018, nuclear power generated by 19 commercial reactors accounted for approximately 15% of Canada’s electricity supply. Despite Canada being a Tier 1 nuclear nation with a full-spectrum capabilities in mining, research and reactor construction, the issue of nuclear waste disposal continues to remain obscure. As of 2022, all two million high-level radioactive spent fuel bundles produced since the first reactor entered service in 1968 remain in temporary onsite storage at the plants were they were used.

Identifying and developing long-term storage solutions for nuclear waste spans decades, and progress has languished due to changing political and social attitudes and the lack of a centralized approach.

Despite such persistent hurdles to nuclear waste disposal, the Trudeau government initiated a roadmap to facilitate the development of Small Modular Reactors (SMR) in 2018. SMRs are next-generation reactors producing less than 300MW and are increasingly proposed as part of the energy transition from fossil fuels. From an environmental policy standpoint, promoting the construction of new reactors is inconsistent with the need to develop a permanent storage solution for existing high-level nuclear fuel.

SMR Roadmap

The Roadmap portrays SMRs as a pivotal technology in the “clean energy transition” because they are smaller, simpler, and cheaper than conventional reactors, not because they provide benefits in terms of nuclear waste management. A 2022 study by researchers from Stanford and UBC found that the volume of SMR nuclear waste may be greater by factors of 2 to 30 relative to existing reactor designs.

Furthermore, molten-salt and sodium-cooled SMR designs utilise highly corrosive fuel and coolants that become highly radioactive, adding to the nuclear waste disposal problem. On volume-based metrics and decay heat power evaluation, the highly concentrated waste generated by SMRs may exacerbate the challenges of nuclear waste management and disposal.

The untested nature of SMRs is also arguably incompatible with the initial design of the Nuclear Fuel Waste Act (NFWA). The NFWA provided the framework for the long-term management of radioactive waste and underpinned the creation of the Nuclear Waste Management Organisation (NWMO). As enacted in 2002, the NFWA operates on a “polluter pays” principle by which waste owners are responsible for funding, organizing, managing and operating nuclear waste storage sites. In practice, nuclear energy operators established trust funds to finance the long-term management of used fuel.

The present framework was developed to dispose of nuclear waste generated by existing CANDU nuclear reactors and was not designed for SMR reactors. Without an operational SMR reactor in existence today, there is uncertainty around the waste types and costs associated with SMRs. Even without unexpected delays, the OPG Darlington New Nuclear Project will not become operational as Canada’s first SMR until 2028.

Despite labelling the technology as “revolutionary,” the roadmap does not treat the regulatory framework to accompany any deployment of SMR with the same vigour.

Delays and Inaction

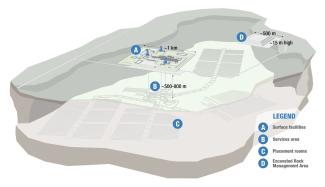

Currently, the nuclear waste management policy recommended and implemented by the NWMO is Adaptive Phased Management (APM), which combines both a technical and management system element. The technical element aims to develop a deep geological repository (DGR) to contain radioactive waste for tens of thousands of years, but this remains a remote and highly controversial prospect. Despite being initiated in 2010, the NWMO’s planning for deep geological storage remains in Step 3 of a 9-step site selection process.

Most recently, in 2020, the Saugeen Ojibway Nation finally rejected an OPG proposal for a DGR to store low- and intermediate-level waste, 15 years after it was first proposed. The selection and ultimate development of a storage site for high-level waste would encounter even greater political, legal, and social hurdles.

The withdrawal of OPG’s DGR proposal at South Bruce without a legal challenge reveals the difficulty of overcoming the duty to consult enshrined in the Constitution. Given the complexity, toxicity and longevity of a DGR, a legal challenge based on breach of the duty to consult and accommodate will likely arise once NWMO selects a site in 2024.

Such a challenge would be premature before a final decision by the NWMO. When considering the environmental and safety challenges arising from Canada’s adoption of SMR technology, the prospect of technical and legal delays to this multi-decade process should be welcomed.

Moreover, the APM contemplates the construction, operation and monitoring of radioactive waste storage over a period of approximately sixty years -- a tiny portion of the lifespan of the hazard. It is critical that Canada adopt a future-proofed approach and have the right solution for permanent nuclear waste disposal.

A Way Forward

Resolving the competing aims of the SMR Roadmap and NWMO waste management will require a revised regulatory framework that accounts for the nuclear waste impacts from SMR technology. In its current form, the NFWA delegates responsibility for the long-term management of Canada’s nuclear fuel to the NWMO. The NWMO is a private organisation established by Canada’s nuclear energy corporations. By design, it is tied by ownership to the nuclear industry.

In the realm of nuclear waste disposal, there is no independent entity dedicated to overseeing the disposal of radioactive waste. Currently, regulatory oversight on nuclear waste overlaps between the private NWMO and the federal Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC). A dedicated public agency would clarify regulatory responsibility for nuclear waste disposal, ensuring that NWMO and any storage solution are accountable to public stakeholders rather than nuclear industry shareholders. Such a regulatory regime already exists in Germany, where the federal agency for nuclear safety (BMU) is complemented by a dedicated federal nuclear waste management authority (BASE). Although a “polluter pays” model implemented by the nuclear industry itself may be sufficient for the temporary storage of nuclear waste, the oversight of the development of a DGR should have public interests as the utmost priority. In its current form, the regulatory regime of the NWMO creates a conflict of interest as regulatory oversight over nuclear waste is effectively controlled by the nuclear industry.

The NWMO has opened a pathway towards a long-term solution to Canada’s nuclear fuel waste, but the advent of SMR technology complicates the development of a DGR. In the interests of futureproofing the facility, it would be short-sighted to pursue the development of a DGR without a complete understanding of the nuclear waste generated by SMR technology.

The NWMO should postpone the site selection, design and construction of a DGR until the regulatory regime is tailored to accommodate SMR waste disposal. A delay will also enable the government to avoid or resolve potential legal challenges based on the duty to consult.

In short, Canada needs to act on its long-term plans for nuclear waste only when a mature understanding of SMR and the appropriate regulatory regimes are in place.

- Centre for Law and the Environment